Nuclear Fusion Powers Tomorrow’s Grid

The Ultimate Energy Frontier: Why Fusion is the Future

Nuclear fusion the process that powers the sun and stars is often described as the Holy Grail of energy. It involves forcing atomic nuclei to merge, releasing colossal amounts of energy without producing long-lived radioactive waste or the greenhouse gases associated with fossil fuels. For decades, fusion has remained the domain of complex, government-funded physics experiments, perpetually described as being “30 years away.” However, the landscape has fundamentally changed. Breakthroughs in plasma science, coupled with an unprecedented surge of over $10 billion in private investment, have accelerated the timeline. Fusion is no longer a distant dream; it is rapidly becoming a commercially viable, disruptive energy source poised to redefine the global power grid by the mid-2030s.

The core promise of fusion is simple yet revolutionary: it offers an abundant, carbon-free, and inherently safe path to generating base-load electricity. Unlike solar and wind, which are intermittent, or nuclear fission, which requires complex waste management, fusion utilizes readily available fuels (deuterium from water and tritium, which can be bred) and, when successful, produces helium and a stream of high-energy neutrons. This article comprehensively explores the scientific principles, the leading technological contenders, the immense engineering challenges, and the geopolitical and financial implications of the global race to commercialize fusion power, appealing directly to audiences interested in clean technology investment and next-generation energy policy.

The Scientific Principle: Replicating the Stars on Earth

Harnessing fusion requires creating and controlling a state of matter known as plasma, a superheated, ionized gas hotter than the Sun’s core. To achieve a self-sustaining reaction that produces more energy than it consumes (a condition known as ignition or scientific break-even), three critical physical criteria must be met, often referred to as the triple product: temperature, density, and confinement time.

A. The Fuel: Deuterium and Tritium

The primary reaction targeted for first-generation commercial reactors is the fusion of two hydrogen isotopes: deuterium (D) and tritium (T).

A. Deuterium Availability: Deuterium can be extracted cheaply and abundantly from ordinary water, meaning the fuel source is virtually limitless. The energy from the deuterium in just one gallon of seawater is equivalent to the energy from 300 gallons of gasoline.

B. Tritium Breeding: Tritium is radioactive with a short half-life (around 12.3 years) and is scarce naturally. Therefore, fusion reactors must be designed to breed their own tritium within the reactor walls using a blanket rich in lithium, which captures the high-energy neutrons produced by the fusion reaction. Achieving a sufficient tritium fuel cycle sufficiency is one of the major engineering hurdles.

C. Reaction Output: The D-T reaction yields a neutron and a helium nucleus (an alpha particle). The alpha particle, electrically charged, remains trapped within the magnetic field, providing the heat to sustain the plasma temperature, while the neutron, which carries about 80% of the energy, escapes to be captured by the lithium blanket to generate heat for steam turbines.

B. The Confinement Challenge: The State of Plasma

Plasma confinement is the monumental task of isolating the superheated fuel which must reach temperatures exceeding 150 million degrees Celsius from the reactor’s physical walls. Any contact would instantly cool the plasma, stopping the reaction, and damaging the containment vessel. Two major technical approaches dominate the global effort: magnetic confinement and inertial confinement.

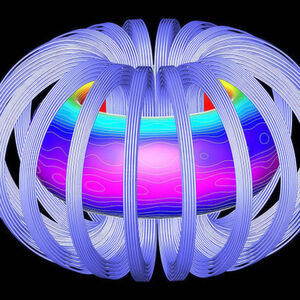

A. Magnetic Confinement (MFE): This approach uses incredibly strong magnetic fields to corral the hot, charged plasma particles. The particles spiral along the magnetic field lines, creating a magnetic “bottle” that isolates the plasma from the surrounding vacuum vessel. This is the method used by the most prominent fusion concepts, the tokamak and the stellarator.

B. Inertial Confinement (IFE): This method involves compressing a tiny pellet of D-T fuel using powerful lasers or particle beams until it ignites, simulating a microscopic, pulsed explosion. While historically government-led, breakthroughs like those at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) have shown the potential of this high-gain, pulsed approach, achieving scientific break-even (where the fusion energy output exceeds the energy delivered to the fuel) in laboratory settings.

Leading Reactor Designs: Tokamak Versus Stellarator

The majority of global fusion research and private funding is focused on two designs within the Magnetic Confinement Ensemble (MFE): the Tokamak and the Stellarator. Both utilize a toroidal (donut-shaped) chamber but differ fundamentally in how they achieve plasma stability and continuous operation, creating a critical competitive dynamic in the commercial race.

A. The Tokamak: The Scientific Frontrunner

The tokamak (a Russian acronym for toroidal chamber with magnetic coils) is currently the most scientifically developed and highest-performing fusion concept. It has achieved the highest temperatures and energy confinement times to date, with ITER (the world’s largest fusion experiment currently under construction in France) being the most prominent example.

A. Operational Principle: The tokamak uses two primary magnetic field components: a toroidal field generated by external coils, and a poloidal field generated by a large electric current induced inside the plasma itself. This internal current provides the necessary “twist” to stabilize the plasma.

B. Key Advantages: The tokamak design is geometrically simpler than the stellarator, and the internal plasma current significantly contributes to plasma heating and confinement. Its scientific history is deeper, offering more data for predictive modeling.

C. Critical Disadvantage: Pulsed Operation: Because the plasma current is induced via a central solenoid (similar to a transformer), the current cannot be sustained indefinitely. This forces the tokamak to operate in a pulsed mode, making it challenging to run a commercial power plant that requires continuous, base-load power output. Furthermore, the internal plasma current is the source of frequent disruptions rapid, catastrophic losses of plasma confinement that can severely stress the reactor vessel.

D. Spherical Tokamaks: A variation that uses a much tighter, lower aspect ratio (a more spherical, cored-apple shape) which allows for higher plasma stability at smaller sizes, a concept championed by the UK’s STEP project.

B. The Stellarator: The Engineering Solution

The stellarator, invented in the 1950s, has emerged as a major commercial contender due to its inherent advantages in continuous operation, despite its complex geometry. It represents a more recent and potentially less risk-prone engineering path to fusion.

A. Operational Principle: The stellarator eliminates the need for the internal plasma current. Instead, the necessary magnetic field twist is generated entirely by complex, non-planar external coils with twisted geometries. This external control is achieved through advanced supercomputing optimization.

B. Key Advantages: Continuous and Stable: Because it relies solely on external magnets, the stellarator can run in a continuous, steady-state mode, ideal for base-load power generation. Furthermore, without a reliance on the internal current, stellarators are inherently more resistant to disruptive instabilities, making them safer and easier to operate commercially. This stability is a significant selling point for utility companies.

C. Critical Disadvantage: Engineering Complexity: The highly complex, three-dimensional geometry of the external coils makes stellarators significantly harder and more expensive to design and manufacture with the requisite precision. The German experiment Wendelstein 7-X (W7-X) is the world’s largest stellarator and a key demonstrator of its physics viability. The recent adoption of High-Temperature Superconducting (HTS) magnets is making the complex coil systems more feasible for smaller, commercial-scale stellarators.

D. Comparison Summary Table:

| Feature | Tokamak | Stellarator | Commercial Advantage |

| Magnetic Field Twist Source | Internal plasma current & external coils | Complex, external coils only | Reliability/Simplicity of operation |

| Operational Mode | Pulsed (with current drive extensions) | Continuous (Steady-State) | Continuous operation (Base-load) |

| Plasma Stability | Prone to Disruptions | Inherently Disruption-Free | Operational safety |

| Design Complexity | Easier to design/model | Extremely complex to design/manufacture | Cost/Time to build |

| Development Status | Most well-researched, highest performance achieved | Scientifically less mature, recent design breakthroughs | Time-to-market |

The Engineering Hurdles to Commercialization

While scientific feasibility (achieving $Q>1$, or scientific break-even) is increasingly demonstrated, turning a physics experiment into a reliable, economically viable power plant requires overcoming unprecedented materials and systems engineering challenges. These challenges are crucial to discuss in an SEO-optimized article as they represent high-intent search queries from engineers and investors.

A. The Neutron Problem and Materials Science

The 14 MeV neutrons released by the D-T fusion reaction are the source of energy, but they also represent the single biggest engineering challenge. These highly energetic, neutral particles escape the magnetic field and bombard the reactor’s inner wall, leading to two major problems: material degradation and induced radioactivity.

A. Neutron-Resilient Materials: Standard steel alloys used in fission reactors cannot withstand the cumulative damage caused by the constant bombardment of fusion neutrons. This damage leads to embrittlement, swelling, and thermal stress, significantly shortening the lifespan of the reactor’s inner wall and blanket modules. Developing new neutron-resilient materials, such as advanced tungsten alloys or specialized ceramic composites, is a massive research priority.

B. First Wall and Divertor Erosion: The divertor is the component designed to channel excess heat and impurities out of the plasma chamber. It is subjected to enormous heat loads—comparable to the heat flux experienced by a spacecraft re-entering Earth’s atmosphere—and constant erosion from the plasma itself. Innovative solutions, including the use of flowing liquid metals (like lithium or tin), are being explored to create a self-healing, regenerative first wall that can withstand these extreme conditions.

C. Induced Radioactivity: Although fusion does not produce the long-lived, high-level waste of fission, the neutron bombardment induces radioactivity in the reactor’s structural components. The key is developing materials whose induced radioactivity decays to safe levels within decades (rather than millennia), enabling simpler, lower-cost decommissioning.

B. Tritium Fuel Cycle and Plant Efficiency

Successfully operating a fusion reactor requires closing the tritium loop: producing, extracting, and recycling tritium fuel fast enough to sustain the reaction, while also maintaining an efficient energy conversion process.

A. Breeding Ratio and Extraction: The Tritium Breeding Ratio (TBR) must be greater than one (TBR > 1) to ensure the reactor produces slightly more tritium than it consumes. This requires optimizing the lithium-containing blanket design, known as the fusion blanket. The tritium must then be efficiently extracted from the blanket and impurities removed from the plasma exhaust, posing complex chemical engineering problems.

B. High-Efficiency Heat Exchange: The reactor’s heat (captured by the blanket) must be transferred to a coolant to drive a conventional steam turbine. The entire system must operate with high thermal efficiency to maximize the net electricity output and reduce the overall cost of energy. This is where the overall system efficiency, engineering must significantly exceed scientific to be commercially viable.

C. High-Temperature Superconducting (HTS) Magnets: The massive magnetic fields required for confinement are now being made possible by the rapid development of HTS materials. These magnets can operate at significantly higher magnetic field strengths and smaller sizes than traditional low-temperature superconductors, dramatically reducing the size and cost of future commercial reactors.

The Commercial Race and Investment Landscape

The final, decisive challenge is transforming a scientific marvel into an economically competitive and profitable power plant. The transition from government-led research (like ITER) to a vibrant, private-capital-driven industry is the single greatest accelerator of the current fusion timeline. The total private investment in the fusion industry has already exceeded $10 billion, signaling market confidence.

A. Private Fusion’s Disruption

Private companies are bypassing the decade-long, step-by-step scientific approach of state-funded labs, adopting faster, risk-tolerant, and more diverse engineering strategies to reach commercialization quickly.

A. Diversified Technological Pathways: Unlike the traditional focus on large, low-magnetic-field tokamaks, private firms are exploring alternatives that offer potential advantages in size, cost, and complexity. These include compact spherical tokamaks, stellarators utilizing HTS magnets, and various forms of Magnetized Target Fusion (MTF) and Field-Reversed Configurations (FRC).

B. Shorter Timelines and Milestones: The industry is moving from decades-long research programs to concrete, achievable milestones. Many private companies are now targeting the construction of pilot fusion power plants that achieve net electricity output (where the electricity generated is greater than the electricity required to run the entire plant) by the early to mid-2030s. This accelerated timeline is a key factor attracting venture capital and large-scale sovereign funds.

C. AI and Computational Power: The sheer complexity of plasma physics is being managed by advanced computation. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is now essential for optimizing the highly complex magnetic fields of stellarators, predicting and mitigating tokamak instabilities, and designing neutron-resilient materials, dramatically speeding up the design and operational phases.

B. Economic and Regulatory Frameworks

For fusion to compete with established energy sources, its levelized cost of energy (LCOE) must be competitive, and the regulatory environment must be clear and supportive.

A. Low Cost of Fuel and High Capacity Factor: The operational cost of fusion fuel is negligible, and as a base-load power source, it can achieve a high capacity factor (the percentage of the time a power plant runs at maximum capacity), offering high utilization and predictable revenue streams, which appeal to utilities.

B. Streamlined Regulation: Regulators, particularly in the US and UK, are developing bespoke regulatory frameworks for fusion, distinguishing it from the stringent rules governing nuclear fission. This tailored approach focusing on the lower, short-lived radioactive inventory of fusion aims to facilitate speedier licensing and deployment.

C. Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs): Early signals of market readiness are emerging. Major energy consumers, including large data centers and technology companies (many of whom are also AI investors), are exploring early power purchase agreements with fusion developers, indicating a tangible market demand for clean, reliable base-load power.

The Profound Global Impact of Fusion

A successful commercial fusion reactor represents more than an energy breakthrough; it is a geopolitical and societal game-changer that addresses climate change, energy poverty, and global stability.

A. Environmental and Safety Advantages

Fusion offers inherent safety and unparalleled environmental benefits compared to all current base-load technologies.

A. Zero Carbon Emissions: Fusion reactors produce no greenhouse gas emissions or atmospheric pollutants during operation, offering a direct, powerful tool for decarbonization of the global energy supply.

B. Inherent Safety (No Meltdown Risk): Fusion reactions are inherently self-limiting. If any part of the reactor fails or the plasma containment is breached, the plasma instantly cools, and the reaction stops in milliseconds. There is no risk of runaway chain reaction or catastrophic meltdown, a major public safety advantage over fission.

C. Minimal Waste Management: Fusion waste primarily consists of short-lived radioactive components from the structural materials (activated by neutrons), which decay to safe levels within decades. This eliminates the centuries-long problem of high-level waste storage that plagues nuclear fission.

B. Geopolitical and Economic Transformation

The ability to generate clean, dense energy anywhere in the world would fundamentally shift global power balances and economic development.

A. Energy Independence and Security: Fusion plants can be built where power is needed, without dependence on fluctuating renewable conditions or politically volatile fossil fuel supply chains. This provides unprecedented energy independence for nations, enhancing national security and economic stability.

B. Alleviating Energy Poverty: By offering reliable, scalable power that uses locally sourced fuel (water), fusion could be deployed in developing nations, providing the dense energy necessary for industrialization and lifting millions out of energy poverty.

C. Supporting Energy-Intensive Industries: Industries like high-performance computing, large-scale manufacturing, and green hydrogen production require enormous amounts of stable, clean power. Fusion is the ideal partner for these industries, acting as the power backbone for the next generation of technological advancement, including the burgeoning Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) sector.

The Final Mile of Fusion

The journey from the complex physics of the star’s core to a reliable fusion power plant on Earth is nearing its final, intensive engineering phase. Advances in magnets, materials science, and computational modeling, combined with significant private sector investment, have compressed the historical timeline dramatically. The global fusion industry is no longer aiming for scientific demonstration; it is aiming for commercial profitability by building compact, efficient, and continuously operating pilot plants. The success of this endeavor will deliver the ultimate, sustainable energy solution, ushering in an era of limitless, clean, and safe power that will reshape human civilization and drive economic prosperity for centuries.